There’s a good chance that you’re already very familiar with inflation and the impact it has on your financial future. But have you ever wondered how to calculate inflation? Well, there’s a formula to accurately calculate the inflation rate. Seeing as inflation impacts every one of us and our financial lives, it’s important for us to understand as much about inflation, including how to calculate it, as we possibly can. The good news is that the calculation itself is straightforward and just about anyone can easily apply the formula to determine inflation rates.

There are two ways you may see inflation represented: target inflation rate and average annual inflation rate.

-

Total Inflation Rate: The total rate of change of the consumer price index (CPI) over a given period of time.

((Target Year – Base Year) ÷ Base Year) x 100

or

((T – B) ÷ B) x 100

-

Average Annual Inflation Rate: The annual rate of change of the consumer price index (CPI) over a given period of time

(((Target Year ÷ Base Year)^(1 ÷ Years in Time Frame)) – 1) x 100

or

(((T ÷ B)^(1 ÷ Y)) – 1) x 100

After making the calculations, the answers should be displayed as a percent.

When applying the formulas, it’s important to understand some of the terminology used when describing this seemingly arbitrary concept—although it’s anything but. Here are some terms you should familiarize yourself with:

- Consumer Price Index (CPI): A consumer price index measures the changes in the weighted average prices of consumer goods and services. It’s a useful tool for consumers who want to know if they are paying too much for a specific item.

- Base Year (B): The inflation base year is the CPI for the year you’re comparing the current inflation rate to. For instance, if you’re curious to find out how much the price of milk has gone up since 1980, the base year would be 1980.

- Target Year (T): The inflation target year is the CPI for the end date (typically the present date) that you’re using for calculating inflation. Your target cannot be further in the future than the current year since you’ll need a CPI value for the target year in the calculation formula.

- Years in Time Frame (Y) = the number of years the inflation took place over.

Example

To understand how it works, let’s say a loaf of bread cost $1.00 in 1980 and $2.00 in 2020, forty years later. Based on this example and the above, here’s what that would look like:

- Target Year: T = $2.00

- Base Year: B = $1.00

- Years in Time Frame (Y) = 40 years

Additionally, the annual inflation rate was 1.748% on average. Below is a breakdown of how to calculate this.

STEP | EXPLANATION | FORMULA |

|---|---|---|

1 | Divide the Target Year (T) by the Base year (B) | $2.00 ÷ $1.00 = 2 |

2 | Divide 1 by the number of years the inflation took place over | 1 ÷ 40 years = 0.025 |

3 | Raise the result of step one to the power of the answer to step two | 2^(.025) = 1.01748 |

4 | Subtract 1 to see the answer represented as a decimal | 1.01748 – 1 = 0.01748 |

5 | Multiply the answer by 100 to convert the answer to a percentage | .01748 x 100 = 1.748% |

Practical application of the inflation rate formula

Now, let’s take a look at some actual consumer pricing over the past hundred years. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has inflation listed at 85% since their base year of 1984. No, it’s not an Orwellian standard. They reset the index with weighted averages calculated between 1982 and 1984. Prior to that, prices had multiplied over ten times since 1913.

In 1920, the price for a loaf of bread was just 12 cents. Fifty years later in 1970, that same loaf of bread cost 25 cents. Using the calculation above, that works out to be an inflation rate of 108%. Today, you might pay somewhere around $2.50, and that’s with enriched flour. Whole grain bread, which is what they baked in 1920, is closer to around $4.00 per loaf. According to the inflation rate formula, that’s an increase of 900% in the last 50 years.

Let’s use the formula to calculate something different. In 1920, a pound of butter sold for 70 cents. In 1970, the price was $1.33—that’s a 90% inflation rate. Fast track to 2020 and butter is now selling for somewhere around $3.00 a pound—an inflation of 125% in the last 50 years and nearly 329% since 1920.

While inflation is a small, incremental rate per year, don’t let that trick you. As you can see the long term impact is a very significant one.

Why inflation happens and who benefits from it

There are two main categories of inflation: cost-push and demand-pull.

Cost-push inflation

The first, cost-push inflation, is associated with and caused by rising production costs, which often means raw materials costs. You can usually predict it coming by tracking prices on petroleum products and precious metals, two primary ingredients in manufacturing. Agricultural products, such as cotton and hemp, also play a role.

Demand-pull inflation

Demand-pull inflation on the other hand is something we experience in our own homes every day, supply and demand. For example, the manufacturing costs for your cable provider hasn’t increased, but the demand for their service has caused an increase in their price. The same phenomenon can be seen in the rise and fall of home values. When inventory is low and demand is up, prices increase. This is a prime example of inflation.

Generally speaking, no one benefits from cost-push inflation. Suppliers raise their prices because their costs of manufacturing, production, or just business in general increase. Retailers often experience shrinking profit margins. Demand-pull inflation on the other hand can significantly benefit the service provider or retailer. Their costs haven’t increased, but due to the demand of their product or service they are able to raise their prices and thus improve their bottom line. Neither of these forms of inflation benefits the consumer.

Inflation rate impacts your personal finances and retirement

This is where the inflation rate formula can particularly be important and interesting to you. When interest rates are on the low end, costs to manufacturers and homebuyers are low, which has a significant impact on the inflation rate. The rate of return on your retirement plan and inflation go hand in hand. Once you officially reach retirement, you’ll no longer be making regular contributions —Instead, you’ll be withdrawing those contributions to pay for your retirement living expenses. If inflation is high and market returns go down, you’ll start consuming your principal sooner, which means your retirement fund will be depleting at a faster rate than you might have either planned for or expected.

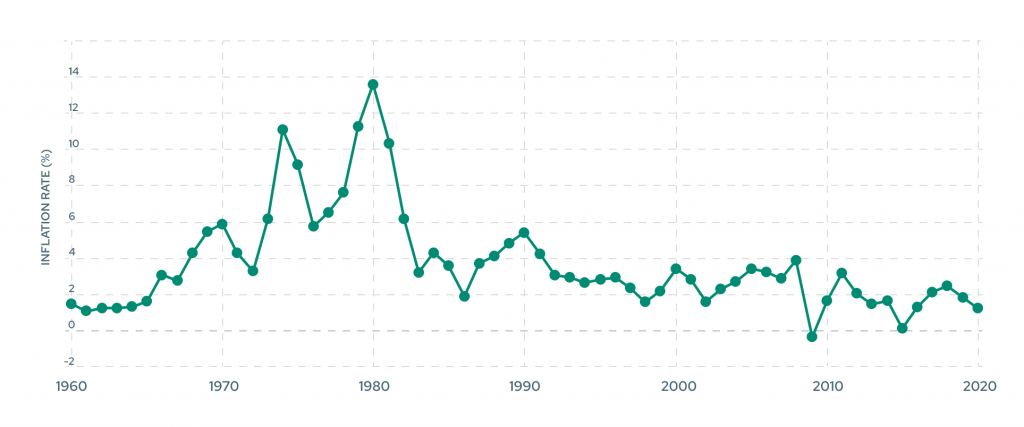

U.S. Inflation Over the Last Sixty Years

The Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed) actively monitors inflation and has a set target of 2% per year. Since 2000 they’ve done a pretty good job. The inflation rate that year was 3.36%. Between 2017 and 2022, the inflation rate averaged 1.51%. However, in May 2022 the inflation rate exceeded expectations and rose to 8.6%, the highest since December of 1981. Additionally, energy prices grew 34.6%, food costs rose 10.1%, and meats, poultry, fish, and eggs rose 14.2% (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Inflation rates are not under your power to control but careful and realistic retirement planning is. Inflation can be a silent retirement killer. This is something many people under-represent, or even forget to represent completely. Fortunately, when you build a financial plan with Savology, your plan will take into consideration inflation, among other important factors, to ensure that you are setting yourself up for financial success in every way possible.